The Making of IGPX 3D Animation Step 1: Modeling

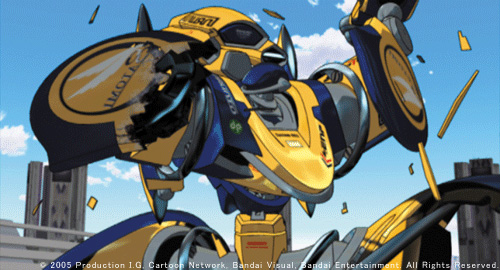

Hyper-dynamic battles between lavishly detailed IG machines running at speed higher than 400 km/h is definitely one of IGPX most impressive characteristics.

For this reason, we decided to get inside Production I.G's 3D Room, and ask the computer graphics team to tell us everything about the creative process behind the astounding mechs of IGPX.

STAFF PROFILE

Miki Yoshida

3DCGI. He's the leader of the IGPX 3D animation team. His main works include: Blood: The Last Vampire (2000), Kaidohmaru (2001) and Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex (2002).

Toshio Kawaguchi

3DCGI. Kawaguchi came to I.G bringing his long experience at Sudio Ghibli. He worked in titles such as Laputa - Castle in the Sky (1986), Porco Rosso (1992), Pom Poko (1994), Jin-Roh (2000) and Windy Tales (2004).

Hiroshi Soma

3D modeling and 3D works. At I.G he worked in Kaidohmaru (2001) and Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex (2002).

Satoshi Shimura

3D modeling. His main works include Innocence (2004), Sol Bianca: The Legacy (1999), and Windy Tales (2004).

Part 01

This time we're doing a feature putting the spotlight on the 3D team. Will you tell us a little about the modeling work that goes on?

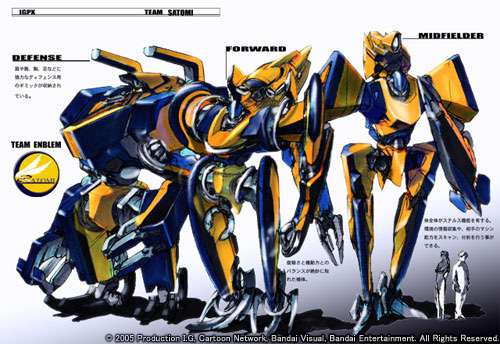

Yoshida: The original designs are created by the designers to conform with the overall work, so the modeler's work is to take those designs as the basis on which to create three-dimensional forms. In regard to IGPX, the director Hongo takes the view that "in the IGPX world, IG machines are designed and produced by different companies, so rather than have one person do the designs, it would be better to have machines that were designed by a number of people". This is the reason why we have two different mechanical designers for this series Junya Ishigaki and Atsushi Takeuchi, who among the staff are respectively known as Ishigaki Heavy Industry and Takeuchi Industrial (lol). They create the designs, and at the stage when their work is done, the modelers in charge review the designs. Then there's an exchange of opinions as we carry on with the modeling work.

Since we can't get anywhere without a 3D model, which is the basis of all 3D work, the modeling is done at the very first stage in the project.

The process of 3D modeling may be somewhat difficult to understand for those who don't use computer graphics tools, but what do you think would be a good example of what it's like?

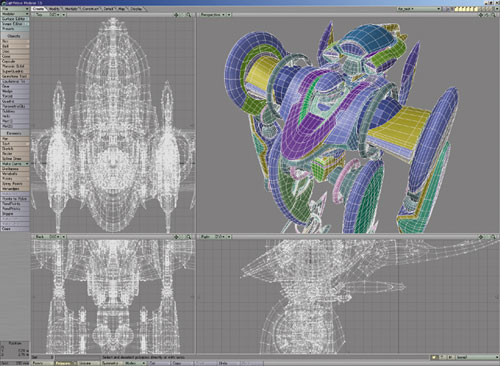

Soma: This depends on the person, but it feels like you're shaping something with clay. We use a software package called "Light Wave Modeler," and this includes a square, box-shaped object tool. You simply place this square down and start cutting parts of it off and stretching bits of it. And after carrying on with this process for a while, it can start to take on the form of a complex machine. This is something that takes a lot of experience to use. It's very hard to explain it in words.

But it's not really the same as sculpting it by shaving off material, is it?

Shimura: It's like adding bits and pieces to it as you create its form. It does feel similar to using clay.

Do you work from basic forms other than the box-shaped object, such as cones or spheres?

Soma: We basically work with box-shaped forms. Sometimes we use spheres, but for the most part we would proceed by doing such things like making cylinder forms out of the boxes.

Shimura: I basically use boxes as well. It's rare that I would use any other form.

How do you work together with the designers?

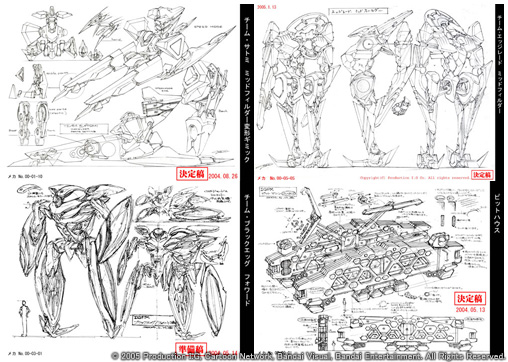

Yoshida: There is one significant difference between the designs of Takeuchi and Ishigaki. Takeuchi's designs are quite detailed when they come to us. I usually ask Shimura to work on them, and they come as images drawn from various angles like the back and sides, and are essentially three-dimensional diagrams. So, while faithfully reproducing these images, we make adjustments to the details as we create the three-dimensional form.

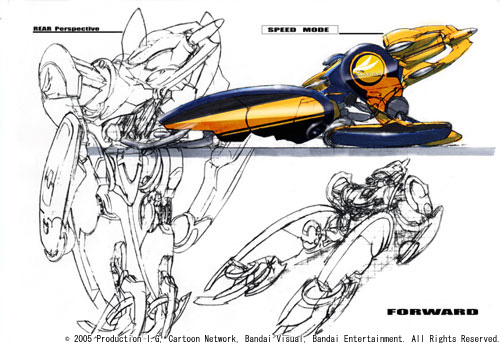

Compared to that, Ishigaki's designs come to us in fairly rough form. So there's a lot of freedom. Ishigaki would ask, "What would a design like this look like in 3D?" And in answer to that, Soma, as the one in charge, would proceed by creating a three-dimensional model based in the design image. So Ishigaki and Soma work together as a team on this as they create the machine.

Shimura: It's not like they planned it that way, right?

Yoshida: I suppose. At first there was talk about cleaning up Ishigaki's designs a bit. But I think his approach was to have us create something that would work in 3D. Soma would do three-dimensional diagrams based on the designs of Ishigaki, who would check it later. And after the process of making changes and corrections here and there, a system that works develops out of it.

With Ishigaki's designs in particular, regardless of the character or whatever technique we may want it to possess, everyone would gather and brainstorm over it, and we would have this energetic exchange of opinion.

Soma: I was even allowed to decide on the colors in some parts while doing the 3D work. There was a lot of freedom.

Yoshida: Normally, when the modeling is checked, only the form and shape would be checked in grayscale. But since we've used some color this time, Ishigaki-san would look at it and in his typical manner say, "This is good!" And so there are quite a few examples of machines that were simply used with those original colors we picked.

We tried pastel type colors for Skylark. In particular, colors that were not used with any of the other teams. In fact, the pink body of the Midfielder was originally a green, but the light blue and yellow of two other machines were the original colors used.

Soma: The three Skylark machines basically have the same form, so coloring was really the way to distinguish between them. We had decided from the beginning that even though the heads would be different, the bodies would structurally be the same. Speaking for myself, I was grateful for this decision as it reduced the amount of work I had to do to about a third. (lol)

Shimura: Ishigaki-san's mechs all have some common elements like you see with Skylark.

Yoshida: This is particular to Ishigaki-san's style, and, although he will use some basic common elements, he is quite bold at changing the parts he wants changed, and can make the changes skillfully. If they look different after all that, then it's good. In terms of work efficiency, that saves us a lot as well. On the other hand, Takeuchi-san's designs differ from one another. (lol)

Part 02

How does it feel when you take a design image that's been brought to you for the first time and you model it into 3D?

Shimura: We'll start off by quickly creating something using the original specs. Then, based on what we've created, we get requests to tweak it here and there, and in time something new is created. So, it's not unusual to have the first and second versions be completely different. We continue this process as long as time permits, so you don't know how it'll turn out when you're still at the first stage.

Yoshida: There are times when some parts are better understood after you model it in 3D. For example, when we rotate a 3D machine around, we might notice that an oblique part may be at the wrong angle or something.

In Takeuchi-san's mind, there's already a clear three-dimensional image of any machine he has designed, I'm sure. When we have him look at renderings of a machine modeled from different angles, he'll come back to us and ask for very detailed changes.

Shimura: Even though Takeuchi-san's drawings are very detailed, there aren't too many modeling failures. There're usually lots of cases where lines that should not be connected actually are. But that's rare in the case of Takeuchi's designs.

I'd say that Team Satomi was the most challenging. That's expected, since they're the lead characters' machines and appear in every episode. But Takeuchi-san checks them thoroughly and we're careful with them. Well, part way through, we did change the way we do the checking. It all goes a lot more smoothly when they can see it moving.

Yoshida: Originally, we had the designers check the three-view images printed on paper. They would mark the corrections directly on that paper. That's how the changes were made.

Shimura: But we'd found it difficult when we'd have to interpret some change based on an ambiguous correction note marked on the paper. It really is much easier for them to make decisions based on the moving model.

Yoshida: There was so much back and forth then. Changes would be made to the first images, and then more changes after that, and this process repeated over and over. The perspective would change depending on the camera angle, so there was a limit to checking it on paper.

Is the actual work something that's done on your own?

Yoshida: Well, when one design setting sheet comes in, we would assign one person to do the work for each of them.

Soma: We quietly work away staring at our monitors. But you start losing your concentration after a while, so you make a point of taking a break. As you're working, you start to realize that your work is getting a little rough. When that happens, you take a break and come back to it the next day or something. They often say that you should let the modeling work lie for a couple of nights before taking another look at it. You really have to review it again with a fresh mind, because sometimes you find yourself looking at it and asking yourself, "What the hell is that?" Sleeping is really the best way to refresh your mind. Or perhaps, going for a walk.

Are there times in the modeling work where you really have trouble?

Shimura: The instructions from Takeuchi-san are basically very clear, so the rest is really a question of how much of a workload it is. When it comes to perceiving the whole image, you have to really rack your brains in order to grasp the image, and sometimes that's a tough process. With Takeuchi's designs in particular, since there are a lot of detailed parts, if you just make something up to start with, the changes you have to make later becomes an unwieldy. Therefore, in the case of Edgeraid, you would have a specific image in mind. You start off with a basic block form, and then you carry on with the work as you get more and more instructions.

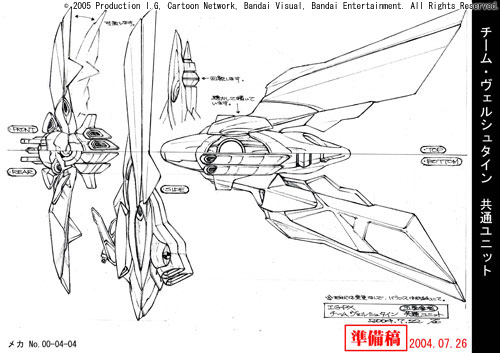

Soma: On the opposite, for the modeling I've done on Ishigaki-san's designs, I get an easy "Okay" from him. In terms of color assignment changes and placing of the stencils, I get my instructions and I make suggestions many times as well. It tended to go quite smoothly that way. I basically like 3D modeling work, so it's not often that I feel like I'm having a tough time of it. However, there was a time about a week ago that I struggled with something and felt kind of stuck. Modeling is not just about creating form, but also about creating a good face and working with polygons in such a way that there is a smooth flow. This is balanced with the form. It's like putting pieces of a puzzle together to get the right matches, and sometimes you get perplexed by it and you spend a long time searching. But it really feels good when you find the correct matches. For example, the other side of the wings on the Team Velshtein machines may look very simple, but it is actually complex. I spent a week racking my brains trying to figure it out. It took a while to get the right balance. And it's also tricky to make changes to a model that someone else worked on. It's best to mess with your own model.

From the various experiences you acquire, you come to develop your own theory. So you work in such a way where you don't disrupt that.

What would happen if each of the machines that each of you (Shimura and Soma) modeled were remodeled by the other?

Shimura: I'd say there's a good possibility that you'd end up with very different machines.

Soma: I suppose. But in this project, I think that we each had a good rapport with the designers. It's not like this was discussed beforehand. It's just simply my fault for injuring my right hand in a motorcycle accident. (lol) I recall that I was working on the Black Egg machines while I was still in rehabilitation.

Shimura: When Soma wasn't able to use his right hand, Takeuchi-san's designs would get completed and they would naturally come to me. After that, we would take turns at the work as the designs were completed.

Yoshida: Thatâs how we split the work in the beginning, but part way through, some of the work was more specifically assigned to one or another. When the habits of the designer match well with the habits of the modeler, you can get a better result that way.

Part 03

What do you pay most attention to when you're doing 3D modeling work?

Soma: I pay a lot of attention to where the components are separated. In a drawing, you might see one line drawn on a component, but you have to think whether it's really a line marked on the component itself, or whether it's a line that marks off that part from some other part. I pay very close attention to those things. Having said that, there are only a set number of polygons I can use, so Iâll just use a line where I can. But what I really would like to do is to build all the components separately and assemble them together as you would with a real machine.

Yoshida: There was mention just now about the number of polygons. With respect to IGPX, I was the one that put the limit on the number of polygons we can use. With the software package we're using right now, when you have at most six machines, a race course and data from other scenes, the machines won't move in the way you want it to if you don't limit the number of polygons. I'm grateful that the modelers have been able to skillfully create the models while keeping within those limits.

I see. "Polygon" seems like rather technical language. Can you explain it to us in simple terms?

Yoshida: Well, would it be easier if I likened it to the number of surfaces a three dimensional object has? For example, we draw curved lines for a sphere, but in actuality, the sphere is made from very small surfaces. The more of these surfaces you use to create a sphere, the rounder the curved lines look. On the other hand, the fewer of these surfaces you have, the more angular the lines look.

The more polygons you have, the cleaner the lines of the 3D object you're creating. But that means more data, and the heavier the processing load. It is the skill of the modeler to be able to eliminate excess data where they can, and that's what we've been getting them to do.

They use the number of polygons needed to show proper motion, so they take whatever they need to give a good appearance. You can really see the differences in the curved surfaces. Sometimes you can see some clunky angles in there. So, I get them to try to use as few polygons as possible in the flat surfaces, and use what they saved there to increase the number polygons to render a good appearance in the curved surfaces.

How does the number of polygons used in IGPX generally compare with those used in other animation productions?

Yoshida: It depends on the software. The one we're using for IGPX is surprisingly weak in terms of processing polygons. If you use too many, the screen will freeze and nothing moves. So compared with other animations, the number of polygons we use is not particularly high. But in those scenes in the animation where we felt that it looked a little rough, we would make additional corrections, and we would even replace a part with another that was rendered with a greater number of polygons.

When you're modeling, how aware are you about the number of polygons?

Shimura: Well, it's not something that you're really concerned with. It has more to do with intuition. If you try to restrict yourself too much, things don't often work out too well. So, you basically do whatever feels right at first and make small corrections afterwards.

Do you anticipate a problem when you see lots of curved parts in the initial drawings?

Shimura: We wouldn't really know what it would take in terms of number of polygons, but we can tell with one look that it's going to be a tough one.

Soma: As you become more familiar with the work, you're better able to gage how many polygons a particular image on the screen has. (lol) Well, you start off the work trying not to worry too much about the number of polygons. I find it easier to do it by shaving off the polygons later. The software has a function that enables curved surfaces to appear smoothly. You use this function to create the round contours, while you scrape away at the parts that don't need as many polygons.

Part 04

When do you feel a sense of satisfaction and accomplishment as a modeler?

Shimura: In my case, I started working as a modeler because I liked Takeuchi-san's designs. So I'm happy when I can bring out his subtle curves and lines in my work. In fact, each part has its own delicate lines. For example, even a box-shaped object that looks like a simple cube would have one its sides slightly shorter or slanting and extending a little. Takeuchi's designs have lots of details like that, so it's challenging to make them look beautiful as finished 3D objects. So when that goes well, I'm quite happy.

I'm a professional modeler, so I'm supposed to make 3D objects that are true to the design drawings. At the same time, I have to clearly express those design details with the lines I create. When I'm successful in doing this, I feel like I've done a good job.

What is your impression of the finished anime?

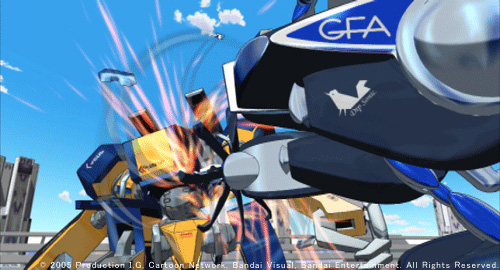

Shimura: Let me see. If you look at Liz' machine, it's designed as a heavyweight mech. I was really impressed with the finished film to see the way the machine used Chinese martial arts moves and yet demonstrated its weight as well as its heavy circular shove attacks.

Soma: And also, I'm thrilled to see some of the gimmicks we included actually being used in some of the scenes. To give you an example, Team Velshtein's forward has a mouth that opens very wide. Very few people know about it. Originally, Ishigaki-san's design specified that it should have "a mouth that opened". There was a note accompanying it that said, "Don't know if we'll ever use it". We decided to go for it, and made separate parts for this purpose. And then it was used once in Episode 13!

Yoshida: For a fraction of a second, there's a close-up of the face with its mouth open. This appears in only one cut. I'm supposed to use the gimmicks that were specially developed. Takeuchi-san always tells me, "suck all the gimmicks out!" (lol)

|  |

Can you tell us something about the process called rig setting, which was used for the 3D objects you've modeled?

Yoshida: Rig setting is a process that positions points that act as joints, which able the model to move. This process shows how well the work is, since it directly affects the actual motion of the object.

Shimura: Yoshida-san had already set the rigs for Team Satomi, so I just made additional adjustments to the basic system according to each machine's gimmicks. Positions of knee joints and other joints are slightly different for each machine even within the same team.

Yoshida: From the initial designing stage, it was decided that there shouldn't be any restrictions to the range of joint movement, since they are robots. So we kind of made those rigs as flexible as possible.

Soma: Yes, we didn't want them to be stiff and fixed, because it would be harder to make them fun. The number of fingers and gimmick types, for example, are different for each team, so each modeler was asked to come up with ideas for the basic parts, and the single ideas have been coordinated in a second phase. Actually, the thighs of the Velshtein machines were designed with triple joints that could be stretched out swiftly, but if we did that, the machines couldn't walk properly. So we added separate rigs.

In the episodes, the machines break down a lot during the race. Do you make models for those scenes?

Yoshida: I asked both of them to make wrecked models even if they only appear in one cut.

Soma: In the beginning, they used to make only one dent per episode, but now that's on a rapid rise. It's fun to think of how I could make wreck them, actually. For example, what if the paint on the carbon fiber is scratched, or if a lightweight, aluminum rod snaps off? I actually break one to see and capture the actual image.

This is going to be the last question. What are the parts that fans shouldn't miss?

Shimura: I've done most of the modeling that I was supposed to do. I'm now doing more scenes that involve moving the robots in normal actions, which I haven't done much until now. I hope you will like it, because I'm putting a lot of effort into it. And also, I've done the Team Satomi machines that appear in every episode, so it is fun to watch them move on screen. Actually, I have only done things like spaceships until this project, and this is the first time I've done robot modeling. I'm happy that I did a good job for a first timer.

Soma: Even for a modeler like myself, Shimura-san's models are really well made, and the work is very carefully done and beautiful. When I compare his models with mine, it's sometimes disheartening. (lol)

Aside from modeling, when we previewed Episode 12, I thought I was going to cry. It's when Team Satomi dodges Velshtein's deadly attack, and Andrei laughs out loud and says something like, "Takeshi's actually pretty sharp." I couldn't stop the tears. There were quite a few people around me who shared the feeling. I hope you don't miss it.

(end)

Recorded on Nevember 15, 2005 at Production I.G, Tokyo.

© 2005 Production I.G, Cartoon Network, Bandai Visual, Bandai Entertainment. All Rights Reserved.

![WORK LIST[DETAILS]](/contents/works/design/images/left_title.gif)

terms of use

terms of use